The Devil and Demons in Medieval Art

Scholars say that no artistic representation of Satan was produced before the sixth century. They suggest that belief in Satan was only made official by the Ecumenical Council of 553. So, until the Devilís existence was certified, the Church had little reason to commission portrayals.

From then on, however, and throughout the Middle Ages,

Descent to Hell, detail (Duccio, 1308)

devils, demons and representations of Hell came to cover entire walls of major churches and were found throughout illuminated manuscripts, in paintings, sculptures and architecture.

While figures of Jesus and the Saints achieved standard, recognizable forms during the Middle Ages, there was no unified depiction of Satan, despite the fact he was a key figure in Christianity.

Illustrations of the Devil were wide-ranging. Satan could appear at any time as man, animal or creature of pure fantasy. When he sought to tempt or fool someone, he might appear as almost human. At other times, he was shown as half-man half-beast, perhaps with horns and a goat's hindquarters, or carrying a pitchfork and with a forked tail. Since Satan's physical appearance was never described in the Bible, images were often based on pagan horned gods, such as Pan and Dionysus, figures common to the religions Christianity sought to discredit or destroy.

As Christianity grew and spread, so did belief in the Devil, who was blamed for illness, accidents, immoral behavior, crop failures and natural disasters. He was also said to be the leader of enemies of the Church, such as heretics, Moslems, and Jews.

In Descent to Hell, a 1308 icon by Duccio that formed part of his Maesta, we see an early depiction of the Devil still showing clear stylistic traces of Byzantine art. This panel illustrates the story, as told in the gospel of Nicodemus, of the time when Heaven was closed to humanity. In those days before the Resurrection, people who led good lives went to Limbo, the underworld as it was known to the ancient Greeks. This picture relates how, following Christ's Resurrection, He descended into Limbo, holding His banner in order to liberate the good souls there.

After breaking down the Gates of Hell

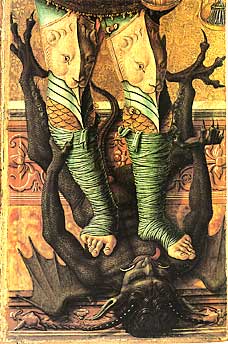

Saint Michael, detail (Crivelli, 1476)

and crushing the hideous looking Devil guarding the door, Christ greets the just, the patriarchs and the prophets of the Old Testament. He holds out His hand to a grey-bearded Adam kneeling alongside Eve, to Abel with his shepherdís crook, to John the Baptist, King David and Moses.

In Carlo Crivelliís 1476 St. Michael, part of a polyptych that comprised the high altarpiece for San Domenico in Ascoli Piceno, we see the fallen angel Lucifer — in the form of a semi-human dragon — who was once head of the Order of Virtues but who lost favor with God and was expelled from Heaven. In this depiction, which occurred frequently in Medieval art, St. Michael, representing Christ in battle with the Antichrist, wears a coat of armor and holds a spear over the horned, winged and clawed Devil.

According to the Biblical story, the powerful angel Lucifer and his followers rebelled against God. The archangel Michael, as the first to refuse Luciferís temptation to join the Rebellion, was appointed captain of the Heavenly Host, Godís loyal army. The two sides battled, and Satan was defeated and cast out from Heaven.

St. Michael, seen here as an archangel with wings, stands victorious and holding a raised sword, prepared to kill the squirming Devil under his feet.

Satan was, of course, allowed to live and to set up his own kingdom in Hell from which he sent other devils to prowl the earth for converts. Medieval art also depicts Satanís fellow rebel angels acquiring tails, claws and other demonic features as they tumble from Heaven. This was the origin of the demonic world, which existed for one purpose only: to tempt humans to turn away from God.

Art during the Middle Ages was primarily an instructional tool of Christianity, and so Hell was a frequent subject. It was shown as a cruel underground world filled with monstrosity, deformity and horrific creatures, designed to strike fear into viewers' hearts. Medieval churches were filled with detailed pictures comparing Heaven and Hell, prominently displayed to congregants, most featuring Jesus, Protector of virtuous souls, enthroned at the top center.

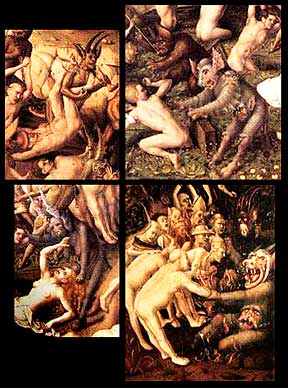

The portrayal of demons in Hell

The Last Judgment, details (Lochner, 1435)

tended to follow forms suggested by Scripture and folklore, which included snakes, dragons, lions and goats. A favorite of the Medieval bestiary were bats and bat-winged creatures. Bats were considered by early Christians as Ďbirds of the Devilí because of their association with the night and similarity to rats. In panels, they symbolized fear and of the powers of darkness and chaos.

Toads (one of the Biblical plagues) and toad-like creatures were often considered demonic and characterized as unclean. Also, since toads eject poison that irritates the skin and eyes, they were used in Christian art as a symbol of death and the underworld. The pig was also unclean and a symbol of lust, greed, and gluttony.

Artists were free to select from these forms according to their fancy, so we see demons with human feet and hands but animal faces and ears; demons with hideous bodies, lizard skin, apelike heads, paws. The purpose was to frighten sinners with threats of torment, and to show how, as they shifted shapes chaotically, demons were the twisted, ugly distortions of what angelic or human nature ought to be.

Images of demons and death produced during the Medieval era were also strongly influenced by the Black Death that devastated Europe in the mid-14th century.

Paintings such as Stephan Lochner's The Last Judgment illustrate the Medieval Church's doctrine as well as the preoccupation with death. In its various scenes, we can sense the frantic atmosphere, experience the images of decomposition, feel the fear reinforced by the Church of the horrors one may face by turning away from God.

Lochner, who actually died

The Last Judgement: Hell, detail

(Fra Angelico, 1431)

during an outbreak of the plague, often painted highly religious, mystical scenes with a Gothic, otherworldly orientation. This tumultuous altarpiece, which closely follows the Netherlandish style, likely hung as an illustration of Justice in the Cologne town hall. Demons, the messengers of Satan — as angels are the messengers of God — are seen gleefully bearing the souls of sinners to the Underworld in the same way angels bear the righteous to Heaven. Lochnerís depiction of a horrifically beautiful scene seethes with the realistic bodies of the naked damned who scream as they undergo torture by legions of distorted, animalistic creatures.

Of course, since Hell was only an abstraction, it also had no standard physical form for artists to follow. The origin of the most representations of Hell derives from the Apocryphal gospels and visions of Medieval monks as the place where the damned were tortured in everlasting flames. A recurring Medieval motif is the entrance to Hell depicted as the gaping jaws of the monster Leviathan, the Biblical creature whose "breath sets burning coals ablaze as flames flash from his mouth."

Hell was often portrayed in the lower right corner of a panel, a spot to which the damned were dragged by the hair or driven by demons, and where they underwent tortures in a manner appropriate to their sin.

In Fra Angelicoís The Last Judgment painted about 1432 for the Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence, Hell is depicted as a fiery crater of torment. The abyss is divided into seven bands, each a place where sins including sloth, greed and lust were punished. The gluttonous wallow in mire while the lecherous burn in a sulpherous pit. Satan sits at the bottom in a lake of fire, covered in thick, black hair and with red eyes, with two half-swallowed sinners dangling from his jaws — plus the unfortunate figure

Our Lady of Succour, detail

(Master of the Johnson Nativity,

ca. 1460)in the center said to represent Judas.

Frequently in Medieval art, Satan was represented by the color red. This symbolized both the fires of hell and the blood of humanity. The Devilís skin was also sometimes red, or he was dressed in red or his hair flamed like fire.

In Our Lady of Succor by the Master of the Johnson Nativity, the subject is an oversized Virgin Mary saving a child conceived in sin during Holy Week from the clutches of the Devil as its mother begs for help.

In this panel from the Velluti Chapel of the Church of Santo Spirito in Florence, the Madonna holds a large club with which she tries to beat the monstrous creature, whoís armed with a three-pronged fork, a principal tool of torture.

Here the Devilís body is entirely covered with fur, and he has claws, a horned head, grotesque face and scorpionís tail, as well as membrane-like batwings.

Itís no accident that artistic representations of Satan reached a peak at the same time as the Church did during the thirteenth century. The concept of the Devil was used by the Catholic Church to extend their influence over moral, social and political conduct. Clear distinctions were made between godly and ungodly. Indigenous religions displaced by the Church were branded as the work of Satan, and the fear of Satan was used as a powerful tool for conversion. Then, as the Renaissance approached and Christianity waned as the dominant social and political force, so too did the depictions of Satan and his minions in art.